China for First-Timers:

A Living History,

a Continental-Scale Country

If your China keywords are “Great Wall, pandas, kung fu, hotpot,” you’re not wrong—but the real China is bigger and more layered. It’s a place where ancient city walls and glass skylines coexist, where a high-speed train can carry you from crisp northern air to subtropical humidity in a matter of hours. This article doesn’t sell routes. It gives you a readable, practical understanding of what China is like—and how daily life works once you arrive.

One country, many worlds: geography that truly changes the experience

The West: China at documentary scale

“Western China” often refers to Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, and parts of western Gansu. The keyword here is scale.

Xinjiang: snow mountains (Tianshan), deserts and oases, plus strong local market culture—often feels like a different continent.

Tibet: high altitude, intense blue skies, and iconic sites like the Potala Palace in Lhasa; altitude adaptation matters a lot.

Qinghai: plateau landscapes and the wide horizon feel around places like Qinghai Lake.

Western Gansu: the Silk Road corridor vibe—where stark terrain and historical heritage sit side by side.

The West can be jaw-dropping, but plan for altitude, big temperature swings, and longer distances.

The South: humid, lush, and close to daily life

“Southern China” can include Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Hainan, and often the southwest such as Yunnan/Guizhou in travel conversations.

Guangxi: classic karst landscapes around Guilin-style scenery—rivers, peaks, villages.

Fujian: coast + mountains, strong tea culture, traditional settlements.

Guangdong: highly urban, yet deeply rooted in food culture (dim sum is practically a lifestyle).

Hainan: tropical island climate and a strong “sun and sea” feel.

Yunnan: dramatic internal diversity—from highland towns to near-tropical vegetation in the far south.

East & North: modern systems + deep historical layers

Eastern coastal regions: you’ll feel the efficiency of metros, high-speed rail, and dense urban services.

The North: colder/drier winters, grand imperial-city storytelling and major historical landmarks.

Also, China uses one unified time zone (UTC+8) nationwide, even though the country spans multiple “natural” time zones—so sunset and daily rhythms can feel different in the far west.

A history bridge for Western readers: align the timelines

Instead of memorizing dynasties, try this mental model—China’s history is long, continuous, and cyclical, often moving through “unification → fragmentation → reunification,” more like system upgrades than complete resets.

Early imperial formation (roughly comparable to the classical world): while the Mediterranean world consolidated through Greek/Roman phases, China also built large-scale administrative systems and capital-centered planning.

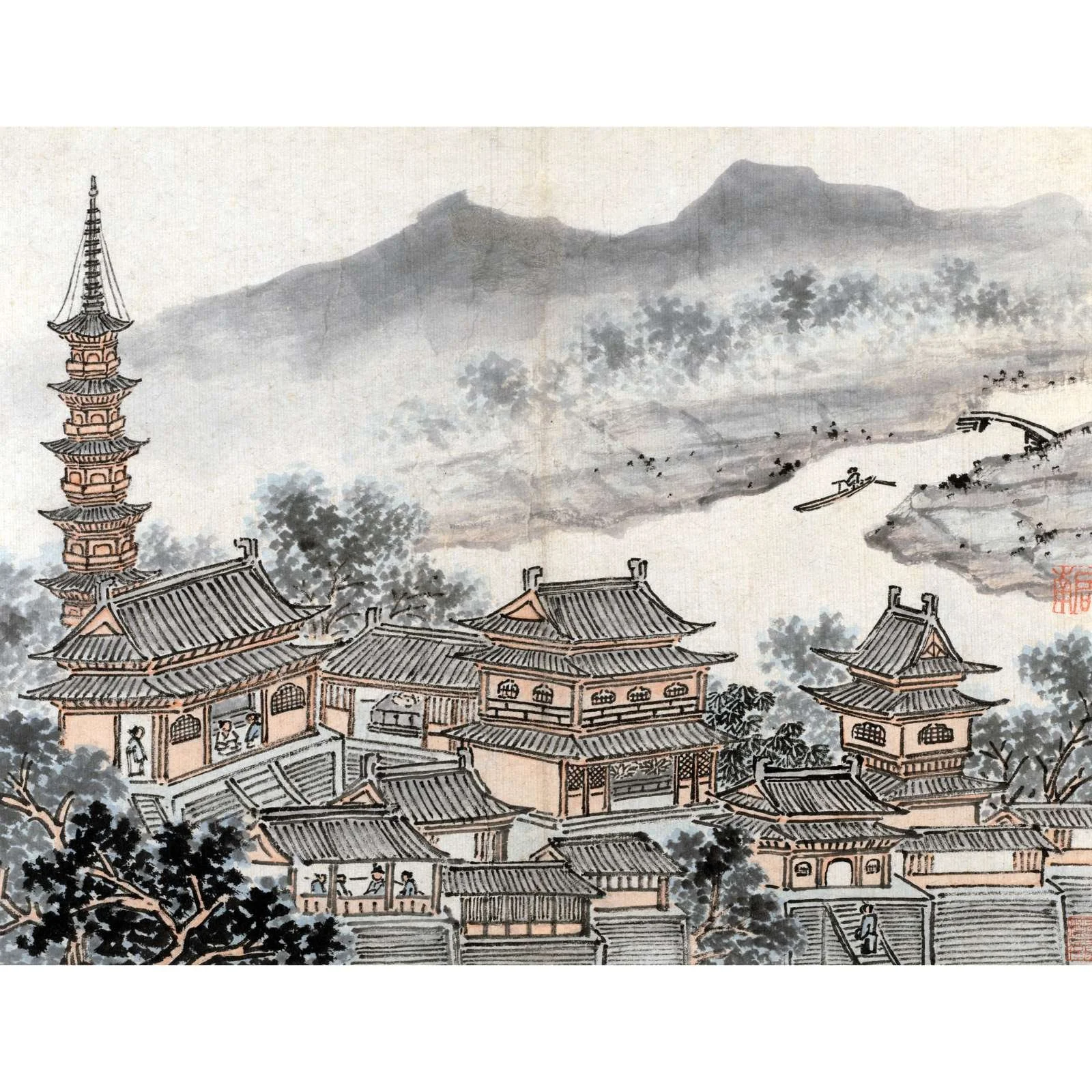

Long imperial continuity (spanning what Europe calls late antiquity into early medieval eras): political shifts happen, but cultural and institutional continuity remains strong—visible in city layouts, ritual spaces, and long-lived traditions.

Commercial and urban sophistication (comparable to late medieval Europe into early modern transitions): vibrant city life, craft traditions, and sophisticated local economies leave traces you still see in historic neighborhoods.

Modern transformation (comparable to the globalizing, industrializing centuries): rapid modernization sits next to preserved heritage, which is why many places feel both ancient and futuristic.

A useful one-liner: China’s history is less a straight line, more a river—changing course many times, but always flowing.

Modern China: highly efficient systems, but your phone is the key

Mobile payments are close to a daily “passport”

QR-code payment is the default in many everyday situations. Cash still exists, but China’s shift toward digital payments is widely observed.

Payment platforms have also expanded support for international cards—e.g., Reuters reported American Express cardholders can link to Alipay and pay at large numbers of merchants.

Credit cards can be less convenient than you expect

It’s not always “impossible,” but many small daily transactions simply aren’t designed around card payments. Don’t rely on a credit card as your only method.

English availability: better in top-tier hubs, limited elsewhere

Hotels and major attractions may offer English support; everyday local settings often won’t. The most effective solution is practical:

save key places in Chinese characters (showing text works)

use a translation app (offline packs help)

keep a bilingual note for your hotel and essential needs

Practical tips and “special realities”: internet, VPN, and China-specific details

Internet access and service availability

Some overseas websites/apps may be unstable or inaccessible due to local internet regulations, which can affect messaging, email, maps, and social platforms.

VPN note (practical, cautious):

China’s stance is widely described as “only approved services are clearly permitted,” often for corporate use; policies and enforcement can shift.

For travelers, the safest approach is to check your embassy/consulate guidance and your service providers’ latest updates, and comply with local laws.

Don’t plan to “set everything up after arrival.” Prepare offline maps, screenshots of key info, and backup communication methods before you fly.

Small China-specific realities first-timers notice

one time zone nationwide

security checks and identity verification in transport hubs and some venues (build in buffer time)

hot water is commonly available and culturally normal

fast pace in cities, but everyday street life (markets/night streets) is where you feel the place

Life essentials: how to call, emergency numbers, what to save

Phone dialing basics

Country code: +86

Chinese mobile numbers are typically 11 digits, starting with 1.

Calling a Chinese mobile from abroad: +86 + 11-digit number (no leading 0).

Emergency numbers in mainland China (display this clearly on your page)

110 Police / general emergency help

119 Fire

120 Ambulance / medical emergency

Many guides also note 110 as a general first number to call in emergencies if you’re unsure.

What to do in an emergency

identify your location using Chinese text (hotel name, street, nearby landmark)

if unsure which number fits: call 110 and explain the situation

contact your hotel front desk and keep your embassy/consulate emergency contact saved